In this story, Language Sciences is delighted to chat with Dr. Christine Schreyer and Dr. Mark Turin about their experience editing the latest special issue of Dictionaries: The Journal of the Dictionary Society of North America. While the journal is dedicated to publish articles on all aspects of lexicography and the importance they bear on dictionary-making, this issue focuses on the reclamation of Indigenous languages through the collaborative approach of dictionary-building.

Please tell us about this issue of Dictionaries.

This issue of Dictionaries centers the work of Indigenous language champions and scholars, particularly anthropologists and linguists, who are engaged in active collaborations on community-based dictionary projects as both forms of language documentation and as essential tools in language revitalization. We are particularly excited to be using the platform of this important and established journal to promote lexicographical work that advances a decolonial agenda in service of language reclamation and revitalization.

We were delighted to have been approached by M. Lynne Murphy, editor of Dictionaries, and the Executive Board of the Dictionary Society of North America in 2022 to serve as guest editors of what has become this special issue. The timing couldn't have been more auspicious, aligning with the first years of the United Nations’ International Decade of Indigenous Languages (2022–2032); the release of UBC’s Indigenous Strategic Plan; a growing momentum within universities (at least in Canada, and perhaps further afield also) to address the cultural genocide perpetrated by Settler-colonial nations towards the Indigenous peoples whose lands, livelihoods and ways of knowing were decimated by the settlement of white Europeans; and the conclusion of our own funded-research project, which we entitled Relational Lexicography: New Frameworks for Community-Informed Dictionary Work. This special issue offers a structured way to highlight the unique role of dictionaries in Indigenous communities and uplift the inspiring work in which Indigenous lexicographers and their partners are engaged.

This issue introduces many relational lexicography projects where the speaker-community actively contributes to dictionaries making. Can you tell us a bit more about the process?

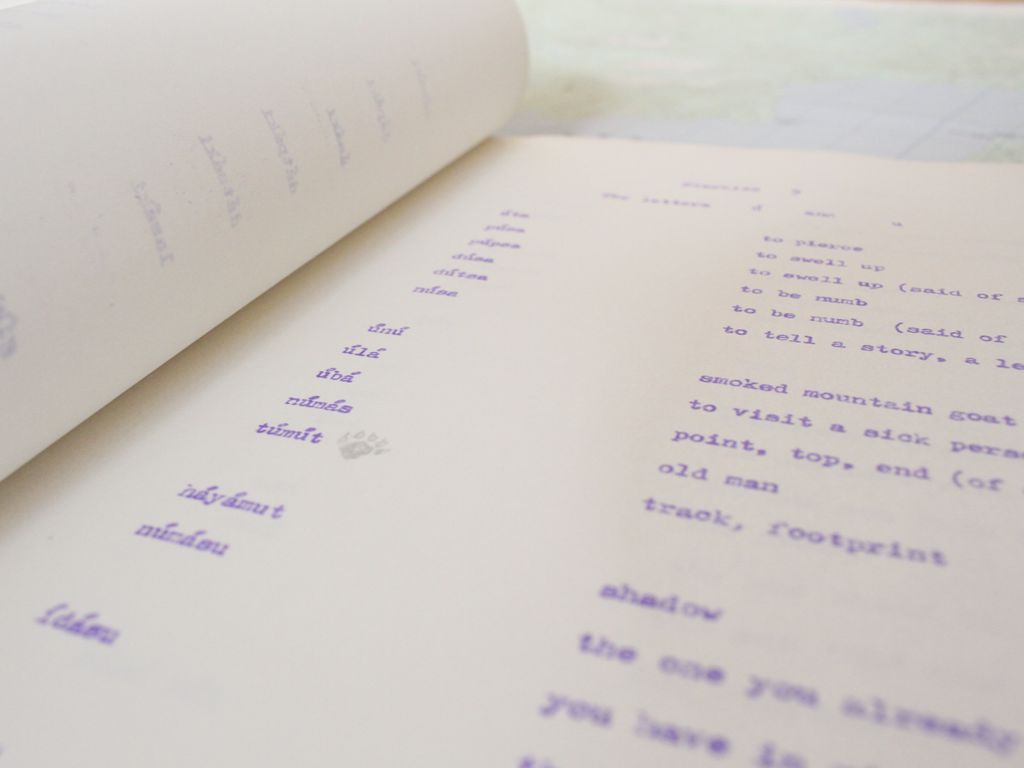

For under-resourced languages spoken by Indigenous communities, dictionaries contain crucial historical, cultural, territorial, and dialectal information. When languages become endangered, dictionaries often become primary tools for language learning. However, in language communities that have few written records, lexicography can be very time-consuming and labor-intensive. In some cases, communities are working to build new dictionaries, the first of their kind for a language or a dialect, while in others, communities are reclaiming legacy language documentation to compile new dictionaries that serve far wider audiences than linguists and trained lexicographers.

While traditional lexicography was conceived and established by speakers of dominant languages, a story generously told over decades in the pages of the Dictionaries journal, this special issue focuses on approaches to dictionary-making that address the needs of under-resourced languages. In increasingly collaborative partnerships, speakers, learners, teachers, and researchers of Indigenous languages are developing protocols, principles, and practices that address the specific requirements and goals of community-informed lexicography.

To address these issues, in our research, we have built a Knowledgebase which hosts a catalog of North American Indigenous language dictionaries alongside information on technologies and digital tools for lexicography. Our paper in the special issue describes the Knowledgebase in detail, but our main goal for this resource is that it be used to assist those engaged in community-based dictionary projects by offering a place to review earlier lexicographical work and to learn about some current technologies that can be used to support dictionary projects. Both the ‘Dictionaries’ and the ‘Technologies’ pages are filterable, making information easier to locate.

There are many dictionary resources available in this issue. Would you like to recommend a few for readers just starting out to learn about the subject?

In this special issue, we highlight the specific needs and strategic goals that speakers of Indigenous languages have for their dictionary projects and reflect on the challenges that communities face in realizing these goals. Many of the articles feature specific Indigenous language dictionaries, including (in alphabetical order): Inuktut, Isga I?abi (also known as Stoney), Maskwascîs Cree, Passamaquoddy-Wolastoqey, Upper Nicola Nsyilxcn, Wendat, and Witsuwit'en, while others described tools or resources used for languages across North America.

All the projects and partnerships in this special issue are examples of what we have termed Relational Lexicography, a shift towards dictionaries that are created by and with speakers and learners of under-resourced languages themselves, which recognize the relationships between speakers, between dialects, and also the relationships that exist between community language workers and academics.

The eleven articles in this collection report on, document, and reflect upon active research projects and collaborations where researchers have enacted, or are continuing to embody and engage with, Relational Lexicography. The articles in this special issue provide examples of dictionaries in which multiple relationships are highlighted, including the relationships between academics and communities, but also the relationship between a dictionary entry and a cultural perspective, dictionary entries and audio files, and between dialects and dictionary entries.

As well, these papers illustrate the complex and intricate relationship between community members and their dictionaries. They illustrate the investments that are made when seeing dictionaries through into publication and the urgent need for lexical resources as tools for language learning and revitalization.